In 2012 Dianne Hoffman, a retired consultant, became a peeping Tom. For five hours a day she watched the antics of a couple, Harriet and Ozzie, who lived on Dunrovin ranch in Montana.

The pair were nesting ospreys, being streamed live as they incubated their clutch of eggs. The eggs never hatched, but the ospreys sat on them for months before finally kicking them out of the nest.

“I do think they experienced grief,” says Hoffman, now 81, who watched the birds from 2,000 miles (3,000km) away in Kennett Square, Pennsylvania.

Hoffman was processing her own grief after the loss of her husband, brother and father, and watching the live streams was how she “rejoined the world”.

“It was a very black time,” she says. Although Ozzie died in 2014, she still watches the nest and its current occupants for an hour a day. “I can’t think of anything the internet has done better for me than these cams.”

Nature-focused live streams, set up near nests, water holes, dens or landscapes to provide a live, constant feed of the natural world, have proliferated over the past two decades, helped by cheap cameras and remote internet connections. The drama of nature – or sometimes the lack of it – is what draws people in.

The seventh season of the TV series The Great Moose Migration from the Swedish broadcaster SVT involved 20 days of continuous live footage, drawing in millions of viewers. Norway’s NRK has aired 18 hours of salmon swimming upstream and 12 hours of firewood burning. A viral fish doorbell allows viewers to watch migrating fish in a lock in Utrecht.

In an increasingly urbanised society, as people spend more time on screens they are less connected with nature. “While technology can draw us away from the natural world, we have also learned that technology can connect us with nature in unique ways,” researchers wrote in a paper published in March.

It came after another study that found nature live streams could “improve the lives of those who cannot leave their homes or live far from natural environments”.

Researchers from the University of Montana first put up a camera focused on Harriet and Ozzie’s nest in 2012. At the end of the breeding season, the owner, SuzAnne Miller, turned it off but scores of people contacted her. “[They said] please don’t do that. We want to watch your ranch,” Miller says. As well as the birds, they could see what was going on behind the nest, she says, and wanted to keep watching.

Initially, Miller did not understand why someone would livestream her doing mundane tasks such as scooping up horse dung. “I did at first find that very odd,” she says. But she added three more live streams of the river, paddock and a bird feeder. It was only when she became ill and was not able to leave the house for six months that she understood the value of it – she too got hooked on live streams of the farm.

If someone leaves a gate open, within minutes a viewer will contact the ranch to warn them. Members watched a vet put down a horse after it slid on ice and broke its neck. The horse’s head lay in Miller’s lap as it died. “Many of these people are older and facing death themselves,” she says. “It got them talking about death.”

The stream has 275 paying subscribers, most of whom have never been to the farm. It cost $8 a month to be a member, and most are older people or those with reduced mobility. Several members have had their ashes scattered there despite never having set foot on the farm, because it became their favourite place in their final years.

Many of these sites allow viewers to message one another or post messages on discussion boards. Established in 1994, FogCam is often billed as the oldest continuously operating webcam in the world. It is a single livestreaming camera that posts an image every 20 seconds, capturing the fog rolling in to San Francisco.

“If you can imagine it, there is probably a live stream about it,” says Rebecca Mauldin, assistant professor at the University of Texas at Arlington. “It is a new area for research, but it’s not a new area; millions of people watch nature live streams.”

But they are not just another form of entertainment – research suggests they could also be good for wellbeing. A new study awaiting publication shows that playing nature-focused live streams increased the wellbeing of some of the older residents in a care home, improving their mood, levels of relaxation, and sleep. A previous study has also found Dunrovin webcams have a “significant positive change” for care-home residents, and could be an “innovative and effective way” to improve wellbeing more broadly.

“I’ve realised it is not just for older adults – there are all sorts of reasons why you might not have full access to nature,” says Mauldin.

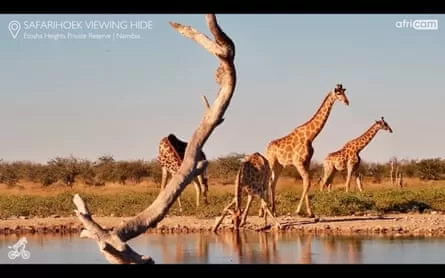

There are hundreds of webcams across 35 of the US’s national parks. The Giant Panda Cam captures activities of animals at Smithsonian National Zoo, and Africam looks at wildlife using cameras across Africa. In the UK, the Wildlife Trusts have 25 live webcams. One of the most popular is the peregrine falcon cam on top of the town hall in Leamington Spa, which had 160,000 views in 2024.

In more remote locations, webcams provide an alternative for people who are unable to visit in person. In Skomer Island off the Welsh coast, the island’s 42,000 puffins are captured on a live stream that had 120,000 views in 2024.

They are also a way of learning more about animal behaviour. Conservationists are using a live cam to study grey seals at South Walney nature reserve, which is free from human disturbance as there is no public access to the beach. “One of our trainees spotted the first-ever seal pup born on the reserve via the camera – a small, white, fluffy pup nestled among the adults,” says Georgia de Jong Cleyndert, head of marine at Cumbria Wildlife Trust.

For some birds such as the ospreys, permanent cameras double up as CCTV. “The osprey cam is primarily for security, to ensure that these protected birds and their nests are safe, and to act as a deterrent to anyone who would wish to harm them,” says Paul Waterhouse, reserves officer for Cumbria Wildlife Trust.

Mauldin says her research shows nature live streams relax people and help them put their own concerns into perspective.

“It also tells a lot about human curiosity – we like to learn, we like a sense of surprise – sometimes it’s nothing, sometimes it’s something amazing. It’s yearning for connection with the world around us,” she says.

What to watch

Keen to start watching nature online? Here are six of the most popular live streams to get you started:

-

Bears going fishing: From late June and throughout July, bears flock to Brooks Falls in Alaska to catch migrating salmon. At times up to 25 bears can be seen onscreen at once (if you can’t wait until June, here are two hours of footage as a taster)

-

Bats on the move: In the daytime, all is quiet on the live stream of Bracken Cave, Texas in the US – but in the evening, you can catch its 20 million resident Mexican free-tailed bats streaming out of the cave to go on the hunt.

-

Baby storks: Knepp Estate in Sussex in the UK is home to a growing population of white storks which bred for the first time in 2020 after an absence of hundreds of years. A livestream shows the nest currently playing host to four fledged offspring: Isla, Ivy, Issy and Ivan. At the time of writing they are tearing up a small dead rabbit.

-

Love Island for osprey: This has been like a series of the hit reality show, with four osprey couples battling for space in one nest at the Loch of the Lowes wildlife reserve in Scotland. After weeks of grafting and being mugged off, two birds have claimed top spot and appear to be putting their eggs in one basket.

-

Going for a drink: This live stream spies on a watering hole in Tembe elephant park at the border of South Africa and Mozambique, and you can watch a steady stream of elephants, lions, rhinos and buffalo stopping by for a sip. After dark, the cam’s night vision lights up a calming, spinning world of moths and fireflies.

-

Live jelly cam: Monterey Bay Aquarium’s jellyfish cam offers a hypnotic experience, immersing you in the serene world of sea nettles, native to the eastern Pacific Ocean. Jellyfish can be seen drifting through, gently pulsating their tentacles as they go.

And if you’re already an avid watcher, share your favourite live stream in the comments below.

Find more age of extinction coverage here, and follow the biodiversity reporters Phoebe Weston and Patrick Greenfield in the Guardian app for more nature coverage