At night, the Lázaro Cárdenas refinery – Mexico‘s oldest, built in 1906 – lights up the city of Minatitlán, in the southern oil-producing state of Veracruz. Gas flaring turns night into day, inhabitants say, while a mix of industrial smells in the air reminds visitors they have arrived in Mexico’s oil and gas heartland.

“It is like Mordor,” said one resident, referring to the volcanic realm in the fantasy novel “The Lord of the Rings” with a tone between humour and resignation. “There are no more dark nights in Minatitlán,” said another local interviewed by Climate Home.

The refinery is a key pillar of Mexico’s state-owned oil company, Petróleos Mexicano (Pemex), and a testament to the firm’s problems with climate-heating methane gas. Pemex has struggled for years to control its rocketing methane emissions despite promises to the contrary and has failed to find an efficient way to use the gas – instead venting or flaring it, which releases methane into the atmosphere.

While its oil production went down in the decade from 2013 to 2023, Pemex now has one of the highest methane footprints per barrel of oil in the world, about eight times that of ExxonMobil and 83 times Saudi Aramco’s, according to local think-tank Mexico Evalúa.

Methane is a greenhouse gas that is around 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide in the first 20 years after it is emitted. Experts say cutting methane emissions is “low-hanging fruit” in tackling climate change.

To that end, a coalition of 160 countries – among them Mexico – have signed a global methane pledge, aiming to reduce emissions by 30% globally by 2030 with respect to 2020 levels. The initiative was first launched in 2021 at the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow.

Pemex has also joined voluntary initiatives like the Oil and Gas Methane Partnership (OGMP) in 2014, under which ten oil and gas giants – including BP, Shell and TotalEnergies – promised to track and evaluate ways to reduce their emissions. Pemex left the partnership when it was ratcheted up in scope and relaunched in 2020. Meanwhile, the company’s emissions have continued to go up.

Ending poverty and gangs: How Zambia seeks to cash in on the global drive for EVs

Pemex’s rising methane emissions, even as its oil and gas production fell, could put Mexico’s ambitious climate goals at risk, analysts warned. The government recently announced at COP29 it will set a net zero greenhouse gas emissions target for 2050, making it the last G20 country to adopt a net zero pledge.

“This new ambition from the Mexican state to reach net zero by 2050 needs to consider the country’s energy policy and Pemex in particular,” said Fernanda Ballesteros, Mexico country manager at the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI).

Like many of the world’s largest economies, Mexico is still due to submit a new nationally determined contribution (NDC) – a climate plan with a 2035 target to cut emissions of all greenhouse gases including methane. Countries are expected to file their new NDCs before September.

Mexican environment secretary Alicia Bárcena has called this round of climate plans “our last hope” to keep global warming to 1.5C above pre-industrial times.

But the country’s new NDC will need to address Pemex’s emissions and show a clear plan for change, Ballesteros said. “[Pemex] is a very relevant actor for Mexico to achieve this [net zero] goal,” she added.

Fugitive methane

Minatitlán is a small city of just over 144,000 inhabitants, including a large floating population from neighbouring states like Oaxaca and Tabasco. Mexico’s southern region made headlines in 2021 when a pipeline rupture caused a gas leak that set fire to the ocean in the Gulf of Mexico.

Around the time of that incident, Pemex promised to reduce flaring (where gas is burned off), as well as venting (where it is released directly) and other types of fugitive emissions such as leaks, as outlined in its 2021-2025 business plan.

A Climate Home analysis of the company’s last four sustainability reports shows that Pemex did manage to reduce flaring, but gas venting and leaks kept growing. And over the past decade, methane emissions still followed an upward trend.

Many methane leaks from Pemex-run facilities – some major – have occurred in recent years, with one in the Deer Park refinery, located in Texas, leaving two dead in 2024.

Climate Home has identified another large leak of methane emissions from a Pemex plant in Minatitlán.

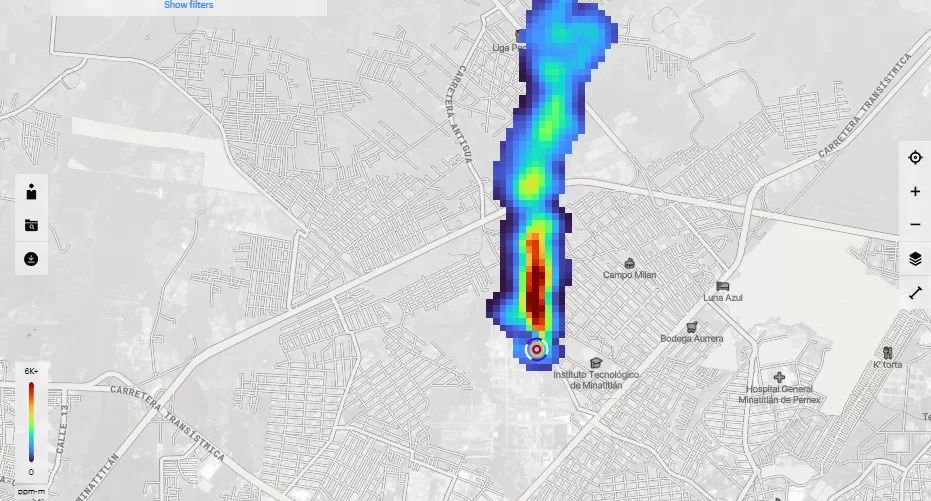

On April 28, 2024, methane monitoring platform Carbon Mapper detected one of the largest methane plumes in the Americas coming from a Pemex plant located right in the heart of the city. Climate Home confirmed that a second satellite data provider, Kayrros, also recorded this plume.

The plume released more than 16 tonnes of methane per hour into the atmosphere, a rate higher than any other single plume detected in oil-producing countries on the continent such as the US or Venezuela over that same year.

Both Kayrros and Carbon Mapper recorded the plume only once, meaning it is not possible to know how long it was active and thus the amount of greenhouse gases emitted into the atmosphere.

The plume was detected over Pemex’s Cosoleacaque petrochemical complex, located 5km from the centre of Minatitlán, near a university and a hospital. The complex contains four ammonia plants, of which only one is currently operational, according to six Pemex workers interviewed.

Cosoleacaque produces ammonia from gas, which is then sold to make fertilisers. This is a business Pemex has recently resuscitated with support from President Claudia Sheinbaum, a climate scientist, in a bid to boost the domestic agriculture sector.

Lula’s government pushes for new oil drilling in the Amazon – where it will host COP30

Pemex plans to invest almost $400 million in reactivating petrochemical plants that were dormant for more than two decades. Cosoleacaque is one of the plants that was restarted in 2023 after operating at minimum levels for years. Workers said there are plans for all four ammonia plants in the complex to come back online, with a second one due to restart around March.

When asked about the leak there, workers suggested it could have gone undetected, because it was active on a Sunday. “If the leak happened on the weekend, there is no way we could have known, because we just work from Monday to Friday,” said one Pemex worker who requested anonymity.

Climate Home contacted Pemex for comment on its growing methane emissions and the plume detected over the Cosoleacaque complex, but did not receive a response.

AMLO effect

Pemex received a boost from the government of Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) in 2018, as he vowed to “rescue the national oil industry again”. Up to then, the company had struggled through years of high debt and plummeting production. Nonetheless, Mexico’s former president described oil as “the best business in the world”.

As the company started to drill more oil under the new mandate to increase production, it found itself with a lot of excess gas it could not take advantage of, mostly due to a lack of suitable infrastructure, analysts said. It resorted to flaring and venting the gas instead.

“Deliberate gas flaring and venting was a problem in the past, but it really worsened during the previous government’s six-year term,” said Adrián Duhalt, a Minatitlán-born energy researcher at US-based think-tank the Texas-Mexico Center.

As deliberate methane releases soared and accidental leaks continued, Pemex’s methane emissions rocketed, almost doubling between 2018 – when López Obrador was elected – and 2022, according to Pemex statistics.

The country’s current president, Sheinbaum, has doubled down on the previous administration’s spending on new oil and gas projects, with the goal of making Mexico self-sufficient in gasoline consumption.

Japan disregarded widespread calls to raise its 2035 emissions goal

Health impacts unknown

While flaring is the most obvious source of emissions, leaks are frequent in Minatitlán, according to residents – but most are only perceptible when ammonia is emitted, because of its distinct smell. The oil and gas industry’s toll on the public health in the area remains largely unknown, analysts said.

Neighbours of the plant interviewed by Climate Home – most of whom have worked in the oil and gas industry themselves – raised concerns over ammonia leaks from the Cosoleacaque complex, which they said caused headaches, dizziness and allergies.

The city was ranked among the top 30 industrial cities in Mexico with worsening health indicators due to air pollution and other types of contamination, according to a 2023 multidisciplinary study sponsored by the Mexican government. Researchers reported rising cases of cancer, kidney failures, birth defects and spontaneous abortions.

In La Oaxaqueña, a neighbourhood immediately adjacent to the ammonia plants, people have learned to live with the chemical smell in the air, which they describe as “that of a public restroom” or “hair dye”.

“Coughing and sneezing is nothing – sometimes you want to run away. I once had to carry my daughter in the middle of the night to the hospital because she was vomiting,” said one woman, describing the effects of an ammonia leak incident. She wished to remain anonymous.

While experts say there is a research gap on the health impacts of oil and gas infrastructure in southern Mexico, a group of NGOs reported similar symptoms last year in the neighbouring state of Tabasco, where they found headaches, nausea and nosebleeds to be common among people living near Pemex plants.

The world’s biggest climate finance coalition is in crisis. Is it worth saving?

On the other side of Minatitlán, flaring at the Lázaro Cárdenas refinery adds to the air pollution, locals said. As the city relies on northern winds to blow away air pollutants from the refinery, the situation worsens when those winds shift or stop.

“Whenever the North [wind] is not blowing, you can really see the cloud of gases on the horizon, and sometimes also perceive the smell,” explained Ramón García, a lawyer who has worked on cases of health complications blamed on the local oil industry.

García said such legal cases are common in the region, especially those related to environmental damage and health impacts – but they almost never reach local administrative courts, as Pemex often settles early in the process, he added.

The details of the cases are also kept secret, García said. In one, involving an oil spill in the region of Papantla, north of Veracruz, the National Agency for Safety, Energy and Environment (ASEA) ordered Pemex to implement an 11-point plan to clean up the spill. When García asked for details of the case in January, he was told they were confidential.

Researcher Duhalt said such issues haven’t “affected the loyalty from the community to the company”.

From an academic standpoint, the Minatitlán-Coatzacoalcos corridor might be considered a sacrifice zone, “but from the standpoint of the head of family, it is just your source of employment,” he added.

Aging infrastructure

Pemex has struggled to control its methane emissions partly due to aging infrastructure and a lack of political will, analysts told Climate Home.

“There are already corporate procedures and technological changes for Pemex to [be able to] emit much less methane. It has been in their plans for years,” said Viviana Patiño Alcala, an energy researcher at think-tank México Evalúa. “But this has not translated into meaningful (emissions) reductions,” she added.

Ballesteros from NRGI noted that the company has focused most of its investments on new projects rather than maintaining existing ones.

In Minatitlán, one worker interviewed near the Cosoleacaque complex said, “it’s all messed up inside, but we are working to fix it”, while a neighbour said it was common to see fires and hear ambulances heading to the plant.

Ballesteros noted that the poor state of Pemex’s infrastructure is reflected in the number of leakage and spill events, which have increased since 2018, rising from 912 recorded events in 2018 to 1,211 incidents in 2023, according to the company’s annual statistics.

It may also be contributing to the high number of worker accidents. In 2023, Pemex reported 129 injuries and 11 fatalities. Its index for accident frequency in that same year was 57% above the industry standard set by the International Association of Oil and Gas Producers (IOGP).

A 2024 report by Reuters showed that the company put off urgent repairs to two of its offshore platforms, causing key components to fail and forcing it to flare large amounts of gas as a result.

“It’s very difficult for this trend [of rising methane emissions] to change soon,” said Patiño Alcala. “If this current administration has been clear in something it is that the environment is important, but it’s more important to provide Pemex with a market.”

Meanwhile, in Minatitlán, residents seem resigned to living with the clouds of gas and the light of the refinery’s flares painting the sky orange.

“With the leaks, even if we don’t see clearly, we know what is in the breeze,” said Irving, a 27-year-old oil worker who lives near the Cosoleacaque plant. “We know how this is, but that’s life for us.”